In the wilds of Northumberland, nestled in the shadow of England’s largest forest and northern Europe’s largest man-made lake is the Environment Agency’s Kielder Salmon Centre. Freshwater pearl mussel expert Dr Ben Strachan outlines the centre’s groundbreaking captive breeding programme, which hopes to secure the future of this critically endangered species.

From the late 1970s, our work at Kielder Salmon Centre to rear and release 160,000 salmon a year has played an important role by stabilising the impressive recovery of salmon stocks in the River Tyne since the industrial revolution.

But it is the centre’s more recent role as a beacon of hope for one of the UK’s most critically endangered species that is drawing increased attention.

The freshwater pearl mussel (Margaritifera margaritifera) is an ecosystem engineer that relies on clean, oxygen-rich, and low in nutrient waters.

The species has long been under threat worldwide due to poaching for pearls, habitat loss, and pollution of waterways primarily through change of land use and wastewater discharge.

The Rivers North Tyne and Rede, in an area renowned for its exceptional natural beauty, are home to the second largest remaining population of freshwater pearl mussels in England.

The Environment Agency is playing a crucial role in conservation efforts to protect the species. Its captive breeding programme is aimed at ensuring the survival of the pearl mussel, which can live for over 100 years, and by extension protecting the health of the area’s aquatic ecosystems.

Adult Freshwater Pearl Mussels were first brought to Kielder Salmon Centre in 2003 and further developments to investigate and introduce a breeding programme were made in 2009.

The first juvenile mussels were collected and successfully reared at the centre in 2017. Since then the team at the centre has worked hard to improve the process.

Our breeding programme replicates the mussel’s complex life cycle in the wild.

The first stage is called encystment and takes place from July through to early August. We use a combination of wild collected mussel larvae, which are called glochidia, and glochidia released on site from wild collected broodstock mussel cared for at the centre.

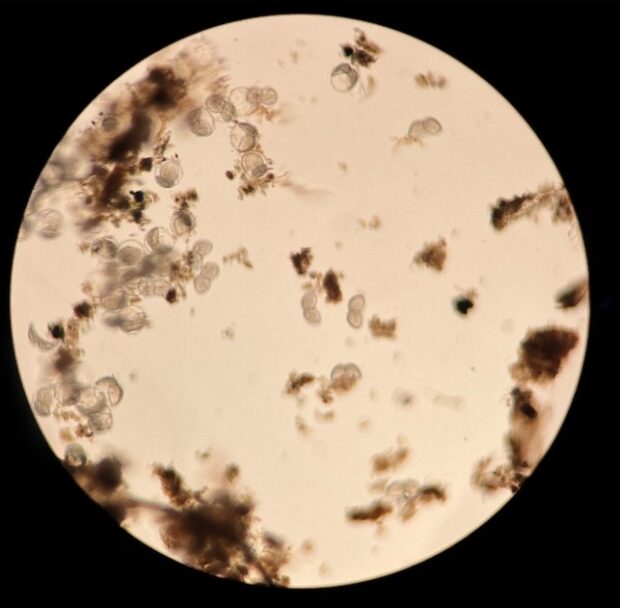

These glochidia, which are miniscule at about 0.06mm in length - are poured into tanks with their host fish, which are trout. The glochidia snap shut on the trout gills and a protective cyst is formed over the mussel larvae.

The second stage is called excystment. This is when the juvenile mussels break free from the cyst on their host fish and sink down to the river bed. At this stage juvenile mussels are around 0.3mm in length. Naturally this would happen from late spring through to early summer as water temperatures rise.

Here at Kielder we place the host fish in special recirculation systems where the water is warmer, which mimics early summer temperatures, thus speeding up the process and spreading the collection of juvenile mussels across the spring.

The collected juvenile mussels are reared in incubator boxes, with optimal feed and temperature. As outside summer temperatures reach the conditions of the indoor incubator, juvenile mussels are moved out to what we call semi-natural ‘flow through’ tanks.

After a few years in flow through tanks, the mussels reach the emergent stage. This is when they move up from deep in the river gravel. At this stage mussels have passed the most vulnerable life stages and are ready to be released back out to suitably restored sites in the wild.

Pearl mussels are ‘vital part of the ecosystem’.

The survival rate for juveniles in the wild has declined over the years, which has led to ageing M. maragritifera populations.

In 2006, surveys noticed the vast majority of pearl mussels observed in the Tyne catchment were older than 40.

Still today, very few juveniles are found in population surveys, emphasising the need for captive breeding alongside habitat restoration aimed at supporting natural reproduction and survival.

The reason for this work is clear – pearl mussels are a vital part of the ecosystem.

A healthy population of mussels is important for water quality. They filter up to 70 litres of water, catching and processing organic matter, supporting and in some cases increasing aquatic insects and fish numbers.

Pearl Mussels also act as an indicator species. This means the health of pearl mussel populations reflects the overall quality of river ecosystems, so the survival of this species is intrinsically linked to the survival of other species.

Our work is helping to protect a whole web of life.

And looking at an even broader picture, the mussels play an important role in the natural heritage that has shaped this unique part of Northumberland.

We are working hard here at Kielder to make sure the pearl mussel populations start to recover to secure the future of this vital species and bring hope for lasting benefits to the surrounding environment.

Follow the Environment Agency Yorkshire and North East, on X and Instagram

2 comments

Comment by Julian P Jones posted on

Great to hear of this work, thank you.

Your efforts could be greatly amplified by better understanding the widespread use and toxicity of veterinary anthelmintics and addressing this. The introduction of ivermectins - which are toxic to many aquatic invertebrates - during 1980s coincided with dramatic declines in eels, salmonids and many other aquatic species.

Anthelmintic residues in manures are mobilised into watercourses following rain.

Comment by Dave Wilkinson posted on

They only give us what they consider good news and hide real problems like falling salmon numbers.

They say elsewhere that too many salmon affect mussel populations in Tyne and Rede yet salmon are endangered now.